Copyright©2023 Misaki C. Kido

Dōgen’s Chinese Poems (69)

Faith in Fresh Blossoms

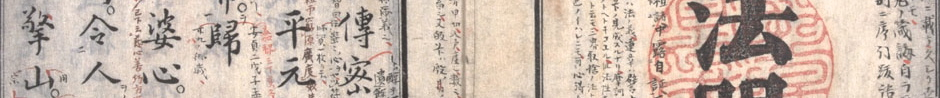

456. Dharma Hall Discourse

「示衆」(示衆)

永平有箇正傳句 (永平に箇の正傳の句有り。)

雪裏梅花只一枝 (雪裏の梅花只だ一枝。)

中下多聞多不信 (中下は多く聞いて多く信ぜず)

上乘菩薩信無疑 (上乘の菩薩は信じて疑うこと無し)

I, Eihei, have this phrase that was correctly transmitted to me:

In the midst of snow, plum blossoms only on a single branch.

Among the middling and lowly, many hear this, but not many believe.

Mahāyāna bodhisattvas trust without doubt.[1]

This is verse 68 in Kuchūgen, and Dharma Hall Discourse (上堂, jōdō) 456 in Volume 6 of Eiheikōroku. This discourse consists only of this verse, without an accompanying speech. This was given in the same month as verse 67, between the 1st day of the 9th month and the 1st day of the 10th month in 1251. This verse in Manzan’s version is the same as Monkaku’s version.

Faith in Fresh Blossoms

456. Dharma Hall Discourse

Dōgen’s master Tiantong Rujing,[2] after years of practice at various monasteries with many masters including his own master Xuedou Zhijian,[3] first became the abbot of Qingliang Temple[4] when he was 48 years old in 1210. Two of his dharma hall discourses given at the temple on Buddha’s Enlightenment Day (on December 8th, in 1211 and 1213) are recorded. The verses which compose these discourses are also quoted in Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō Ganzei (Eyeball). In 1211, Rujing said:

六年落草野狐精、(六年落草す野狐精、)

跳出渾身是葛藤。(渾身を跳出する是れ葛藤。)

打失眼睛無処覓、(眼睛を打失して覓むるに処無し、)

誑人剛道悟明星。(人を誑いて剛に道ふ、明星に悟ると。〉

For six years, a wild fox spirit fell down and stayed in the weeds;

The whole body that leaped out was entangled vines.

When he lost his eyeball, he had nothing to seek,

He cheated people by asserting that he had awakened [upon seeing] the bright star.[5]

On Buddha’s Enlightenment Day in 1213, Rujing said:

瞿曇打失眼睛時、(瞿曇、眼睛を打失する時、)

雪裏梅華只一枝。(雪裏の梅華只一枝なり。)

而今到処成荊棘、(而今、到処に荊棘を成す、)

却笑春風繚亂吹。(却て笑う、春風の繚亂として吹くことを。)

At the time Gautama lost his eyeball,

In the snow there was a plum blossom on a single branch.

Right now, everywhere, thorny branches are growing.

Instead, I laugh at the spring wind blowing vigorously.[6]

Dōgen loves this last verse, particularly the second line: “In the snow there was a plum blossom on a single branch (雪裏梅華只一枝).” In Dōgen’s verse 68, he says that this phrase is what has been correctly transmitted to him. He says so because this is Rujing’s expression about Shakyamuni Buddha’s awakening. For Dōgen, this phrase is the authentic expression of Shakyamuni Buddha’s awakening that has been transmitted from the Buddha to Mahākāśyapa, and down to Dōgen himself through Rujing.

“Losing one’s eye” and “awakening” sound like opposites in our common way of thinking. I think we need to understand what “Gautama lost his eyeball,” means, because Rujing wrote the same thing in 1211 in the first verse on Buddha’s awakening.

To understand this point, it is helpful to take a look at what Rujing said in one of his general sermons (普説, fusetsu), included in a later part of Rujing’s Recorded Sayings.[7] Because this general sermon was also given at Qingliang Temple, it might have been given around the same time as the two dharma hall discourses on Buddha’s Enlightenment Day. In this sermon, Rujing talked about his understanding of shouting (喝, katsu). Since Rujing practiced with many Linji (Jp. Rinzai) masters in addition to his Sōtō master Xuedou, he had much experience with, and a deep understanding of Linji’s teaching and practice. It seems to me that he was criticizing the way Linji monks habitually treated Linji’s teachings as a device (機関, kikan) of the kōan system, in this case “Linji’s Four Shouts (四喝, shikatsu)[8].”

In the sermon, Rujing talked about the six sense-organs, the six objects of sense organs, and the six consciousness:

於日用中。六處發現。在眼曰見。直須抉却眼睛迥無所見。然後無所不見。方可謂之見。(日用の中に於いて、六處發現す。眼に在っては見と曰う。直に須らく眼睛を抉却して迥かに見る所無からしむ。然して後に見ざる所無きを、方に之を見と謂つべし。)

In day-to-day life, the six fields (six sense organs and six objects of sense organs work together as one) become manifested. In the case of eye, we call it “seeing.” We should gouge out our eyeballs right away and let us be unable to see anything at all. After that, there is nothing we cannot see, then we can say that we “see.”[9]

After this, Rujing repeated the same thing about the other five sense fields. This is what “losing one’s eyeball” means in Rujing’s verse. It is interesting—Rujing interpreted even such a simple word and action like “shouting” as the Buddha’s teaching of dependent origination. “Losing one’s eyeball” means that the dichotomy of eye and object of eye dropped off. In the case of the Buddha’s awakening, the Buddha saw the bright star, then he lost his eyeball. His eye was dropped off and only the bright star was there. The Buddha disappeared and became a part of the entire world of the bright star. This is what “losing one’s eyeball” means. On the other side, we can say that when the bright star was dropped off, only the Buddha’s eyeball remained. This is what is called “seeing without seeing” (離見の見, Jp. riken no ken).

I, Eihei, have this phrase that was correctly transmitted to me:

In the midst of snow, plum blossoms only on a single branch.

The first time Dōgen Zenji used the phrase, “plum blossom in the snow,” is in Dharma Hall Discourse 135, given on the winter solstice in 1245. At the end of the discourse, after a pause he said:

Although the plum blossoms are bright amid the fallen snow, inquire further about the first arrival of yang [with the solstice].[10]

That was the first year Dōgen and his sangha conducted their regular practice, including a summer practice period at the newly constructed monastery Daibutsuji in Echizen. That was the first winter Dōgen gave dharma hall discourses in Echizen. Koun Ejō, who compiled the volume 2, added a paragraph after the discourse.

This mountain [temple] is located in Etsu [Province] in the Hokuriku [northern] region, where from winter through spring the fallen snow does not disappear, at various times seven or eight feet, or even more than ten feet deep. Furthermore, Tiantong [Rujing, Dōgen’s teacher] had the expression “Plum blossoms amid the fallen snow,” which the teacher Dōgen always liked to use. Therefore, after staying on this mountain, Dōgen often spoke of snow.[11]

After moving to Echizen, Dōgen has two reasons to appreciate this phrase, “plum blossom on a single branch in the snow (雪裏梅花只一枝).” The first reason is that this phrase is the expression of Shakyamuni Buddha’s awakening, correctly transmitted to him through Rujing. The second is that the plum blossoms are the only flower he can see during winters at Daibutsuji (renamed to Eiheiji in 1246) in Echizen. Even though the entire world is covered with snow, the single plum blossom is the sign of the coming spring. This is also used as a metaphor of “practice and realization are one (修証一如).” Within their practice in the cold winter, realization is already manifested.

In Shōbōgenzō Baika (梅華, Plum Blossom), Dōgen fully expressed the meaning of this phrase. I think Dōgen’s understanding of this phrase is more grandiose and dynamic than Rujing’s. In his general sermon (fusetsu), Rujing expressed that the distinction between subject and object disappear; when Gautama’s eyeball is lost, only a plum blossom is there on a branch in the snow. But Dōgen’s insight is much broader. In the beginning of his comment on this verse in Baika, he said:

Now, the ancient buddha’s dharma wheel is turned to the remotest corners of the entire world, and this is the time for all human and heavenly beings to attain the Way. And [the same holds true] even for clouds, rain, wind, and water, and for grasses, trees, and insects; [indeed] there is nothing that does not receive a dharma blessing [from the ancient buddha’s expression]. Heaven, the earth, and the homeland are turned by this dharma wheel and function vigorously [like jumping fish].[12]

He is talking about the entire world and all beings in it. This is the structure of the entire network of interdependent origination in which all beings are interconnected. A plum blossom is the entire network and the Gautama’s eyeball is also the entire network. When Gautama’s eyeball is lost, the plum blossom is there and all other beings including Gautama’s eyeball are family members of the plum blossom. The plum blossom is itself Gautama’s eyeball. Dōgen says:

“A plum blossom in the snow” is the one-time emergence of the uḍumbara flower. How often do we see our Buddha Tathāgata’s true dharma eyeball, yet miss his wink and fail to smile? Right now, we have authentically transmitted and accepted that the plum blossom in the snow is truly the Tathāgata’s eyeball.[13]

The Buddha’s eyeball that was lost is now blooming in front of him as the plum blossom; Shakyamuni Buddha holds the stalk of an uḍumbara flower and blinks his eyes. Not only the flower blooming at Eiheiji, but all the flowers in the dharma world are the Buddha’s eyeball. We see flowers so many times, but we are not like Mahākāśyapa, so we fail to smile.

Among the middling and lowly, many hear this, but not many believe.

Mahāyāna bodhisattvas trust without doubt.

The third line, “Among the middling and lowly, many hear this, but not many believe. (中下多聞多不信)” is taken from the famous long poem the Song of Awakening (証道歌, Shōdōka).[14] The fourth line, “Mahāyāna bodhisattvas trust without doubt. (上乘菩薩信無疑)” is taken from Shitou Xiqian’s poem Song of the Grass-Roof Hermitage (草庵歌, Sōan-ka).[15] Here, “Mahāyāna” is a translation of 上乘 (jōjō, higher vehicle), an abbreviation of 最上乗禅 (saijōjō Zen), the highest kind of Zen also called Tathāgata’s pure Zen (如来清浄禅, nyorai-shōjō-zen). Saijōjō Zen is ranked above outsider Zen (外道禅, gedō-zen), ordinary people Zen (凡夫禅, bonpu-zen), smaller vehicle Zen (小乗禅, shōjō-zen) , and larger vehicle Zen (大乗禅, daijō-zen) as categorized by Guifeng Zongmi (780–841).[16]

I don’t think I need to explain these two lines. Dōgen Zenji expects that his assembly monks are all bodhisattvas of the highest vehicle.

— • —

[1] Dōgen’s Extensive Record volume 6, Dharma Hall Discourse 456, 409 © 2010 Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, Dōgen’s Extensive Record. Reprinted by arrangement with Wisdom Publications, Inc., www.wisdompubs.org.

[2] 天童如浄, Tendō Nyojō, 1163–227.

[3] 雪竇智鑑, Secchō Chikan,1105–1192.

[4] 清涼寺, Seiryōji.

[5] Okumura’s unpublished translation. Another translation is in Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō Vol. IV, The Seventy-five-Chapter Compilation, Part 4, Chapter 46–60 (The Administrative Headquarters of Sōtō Zen Buddhism (Sōtōshū Shūmuchō, 2023), 284.

[6] Okumura’s unpublished translation. Ibid. 154.

[7] Genryū Kagamishima「天童如浄禅師の研究」(Tendō Nyojō Zenji no Kenkyū, Shunjūsha, 1983), 332–337. I don’t find any English translation of this sermon by Rujing.

[8] The Zen Teachings of Master Lin-Chi (Translated by Burton Watson, Shambhala), 98–99.

[9] Okumura’s translation.

[10] Dōgen’s Extensive Record, 164.

[11] Ibid.

[12] Okumura’s unpublished translation. Another translation is in Shūmuchō translation of Shobognezo, Vol.4, 154.

[13] Ibid. 156.

[14] Another translation is in Commentary on the Song of Awakening (Kōdō Sawaki, translation by Tonen O’Connor, Merwin Asia, 2015), 4.

[15] Cultivating the Empty Field: The Silent Illumination of Zen Master Hongzhi (Taigen Dan Leighton, Tuttle Publishing, 2000), 72.

[16] See, Zongmi on Chan (Jeffrey Lyle Broughton, Columbia University Press, 2000), 103.

— • —

Translation and commentary by Shōhaku Okumura Roshi.

— • —

For further study:

See Dōgen’s Extensive Record.

> More of Dōgen Zenji’s Chinese Poems

Copyright©2023 Sanshin Zen Community