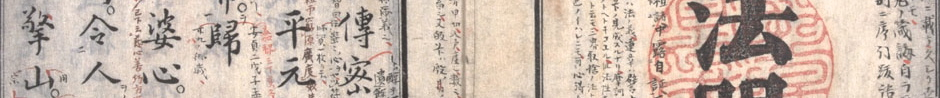

Image credit: Cleveland Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Dōgen’s Chinese Poems (74)

Practice That Continues Beyond Magical Offering

313. Dharma Hall Discourse

「百鳥銜花」(百鳥花を銜む; Hundred Birds Carrying Flowers)

含花百鳥獻牛頭 (花を含んで百鳥牛頭に獻ず。)

投子當初儀賣油 (投子當初賣油を儀う。)

才不才三十五里 (才と不才と三十五里。)

古今道得進將修 (古今道得す進と修と。)

Carrying flowers, hundreds of birds made offerings to Niutou.

Touzi [Datong] appeared to be selling oil.

Talented and untalented are thirty-five miles apart.

People in the past and present have expressed progress and practice.[1]

This is verse 73 in Kuchūgen, and the final part of Dharma hall discourse (上堂, jōdō) 313 in Volume 4 of Eiheikōroku. The short speech prior to this verse is introduced below. This discourse was given between the 15th day of the second month and the 8th day of the 4th month in 1249. Manzan’s version is slightly different from Monkaku’s version in the first and third lines:

銜花百鳥獻牛頭 (花を銜んで百鳥牛頭に獻ず)

Holding flowers in their beaks, hundreds of birds made offerings to Niutou.

銜 (fukumu) means “to hold something in one’s mouth.”

才與不才三十里 (才と不才と三十里)

Talented and untalented are thirty miles apart.

The character 與 means “and.” To change “thirty-five miles” to “thirty miles,” one character is subtracted.

Practice That Continues Beyond Magical Offering

313. Dharma Hall Discourse

This is a short discourse. Before the poem, Dōgen simply introduces a kōan story:

I can remember that before Niutou had met the fourth ancestor [Dayi Daoxin], hundreds of birds brought Niutou flowers in their beaks as offerings. After their meeting, the birds brought no more flowers.

This poem is about the comparing two stories. The first story is about Niutou Farong (牛頭法融, Gozu Hōyū, 594–657) before and after his meeting with the Fourth Ancestor, Dayi Daoxin (大医道信, Daii Dōshin, 580–651). Farong was the founder of Niutou school of Chinese Zen. Historically, it was an independent school, together with Northern and Southern schools. But later, when the orthodox Zen lineage was established, the connection between Daoxin and Farong was made up.

According to the Record of Transmission of the Lamp (景徳伝灯録, Keitoku Dentōroku, compiled in 1004), after Daoxin transmitted the Dharma to the Fifth Ancestor, Daman Hongren (大満弘忍, Daiman Kōnin, 602–675), he visited Mt. Niutou and met Farong. The story says that before he met Daoxin, Farong was always sitting alone on the mountain. Even when other monks approached him, he did not respond. Hundreds of birds holding flowers in their beaks came to offer them to him. Around Farong’s hermitage, some tigers and wolves were walking around. Upon seeing the animals, Daoxin raised his hands as if he feared them.

Farong said, “Is a Zen master like you still afraid of animals?”

Daoxin said, “What did you just see?”

Then, Daoxin wrote the character for “Buddha (佛)” on the rock on which Farong always sat.

Farong looked fearful.

Daoxin said, “Are you still afraid of Buddha?”

Farong did not understand what Daoxin meant, so he made a full prostration to show that he was ready to listen to Daoxin.

This story shows there was some difference between Daoxin and Farong at that point in time. However, the story continues: after he met Daoxin, Farong was transformed.

After hearing the Ancestor’s long dharma discourse, Farong asked a few questions and listened to Daoxin’s answers. Then the Ancestor gave dharma transmission to him. They met only this once in their lifetimes. One important point in Daoxin’s teaching was that there are no triple worlds of samsara to escape from, and no awakening or nirvāṇa to seek after; the great Way is empty and vast: “This being the Dharma you have now come to, without anything lacking, how is it different from Buddha?” Daoxin taught that to practice meditation chasing after some valuable thing was still samsara, even if that valuable thing was awakening (which was Farong’s practice). Instead, Daoxin offered the teaching of sudden enlightenment without gaining anything.

After this story, the Record of Transmission of Lamp text introduces a note about a conversation between a monk and Nanquan Puyuan (南泉普願, Nansen Fugan, 748–835) concerning Farong’s transformation.

有僧問南泉。「牛頭未見四祖時爲什麼鳥獸銜華來供養」。

A monk asked Nanquan, “Before Niutou met the Fourth Ancestor, why did birds and animals come holding flowers to offer them to him?”

南泉云、「只爲歩歩踏佛階梯」。

Nanquan said, “It is only because [Niutou] walked step by step on the stages to the buddhahood.”

僧云、「見後爲什麼不來」。

The monk asked, “After meeting [him], why did they stop coming?”

南泉云、「直饒不來猶校王老師一線道」。

Nanquan said, “Even though they did not come, still, compared with Wang Rōshi, there is a little difference.”[2]

In the original story in the Record of Transmission of the Lamp, it does not say that the birds stopped coming to offer the flowers to Farong after he met Daoxin. But in another version of the same story in Zutanji [祖堂集, Sodoshu] made in 952, it is said that after Farong met Daoxin, mysterious spiritual beings, demons or spirits stopped coming to make offerings to him.[3] Farong was practicing meditation by himself seeking after the attainment of awakening. He was supported by spiritual beings, demons or gods, and animals which came to make offerings to him. But after receiving Daoxin’s teaching, Farong did not seek anything. Then the spiritual beings could not see him, and animals stopped coming to offer things to him. Because his practice became nothing special, nothing mysterious, those beings could not see him.

Dōgen wrote in Points to Watch in Studying the Way (学道用心集, Gakudō-Yōjinshū):

A practitioner should not practice buddha-dharma for his own sake, in order to gain fame and profit, or to attain good result, or to pursue miraculous power. Practice the buddha-dharma only for the sake of the buddha-dharma. This is the Way.[4]

The second story is about Zhaozhou Congshen(趙州従諗, Jōshū Jūshin, 778–897)’s encountering with Touzi Datong (投子大同, Tōsu Daidō, 819–914). While Zhauzhou was traveling, he visited Touzi Datong living in Mt. Touzi. When Zhauzhou arrived at the nearby town of Mt. Touzi, Touzi also came down into the city. They met accidentally, but they did not recognize each other.

Zhauzhou asked a local person if that was Touzi. The person said “Yes.”

When he caught up Touzi, he asked, “Are you the master of [the temple] in Touzi mountain?”

Touzi said, “Please give me a coin for tea and salt.”

Touzi was pretending that he was a beggar and not an enlightened Zen master.

Zhauzhou went to Touzi’s hermitage before Touzi returned.

Touzi returned carrying a jar of oil.

Seeing him, Zhauzhou said, “Having admired Touzi for a long time, when I come, I see only an old oil seller.”

Zhauzhou was teasing Touzi, saying he looked like an ordinary old oil seller, not like a great Zen master.

Then Touzi said, “You see only an old oil seller, but you do not yet know Touzi.”

Touzi meant that Zhauzhou only saw his karmic body and mind (which was not different from a beggar or an oil seller), he did not see his true face as a Zen master.

Zhauzhou asked, “What is Zen master Touzi like?”

Touozi said, “Oil! Oil!”

This time, Touzi pretended to be an oil seller and made a hawker’s cry. I think Touzi is saying that Touzi seeming to be a beggar or an oil seller and Touzi the Zen master are the same but different; different but the same.

Zhauzhou asked, “What is it like to gain life within death?” (死中得活時如何)

Then Touzi said, “It is not allowed to walk in the night, but you should arrive before dawn.” (不許夜行投明須到)[5]

Zhauzhou said, “I am like Houbai, and you are like Houhei. (我早侯白伊更侯黒)”[6]

Zhauzhou praised Touzi, saying he was as mature as himself.

Zhauzhou lived for 120 years and Touzi lived for 96 years. Zhauzhou was 41 years older than Touzi. When Zhauzhou was 81 years old, Touzi was 40 years old. It is said that Zhauzhou traveled after his teacher Nancuan’s death when he was 60 years old and settled at Kannonin temple in Zhauzhou, when he was 80 years old. It might have been possible they met each other, but Touzi was still a young Zen master. In this story, it sounds as if Touzi was as mature as Zhauzhou.

Touzi and Zhauzhou discussed the same point as Daoxin did with Farong. In both stories there is nothing like a mysterious power which attracts a spiritual being or animals. Touzi and Zhauzhou are very much ordinary and down to earth. On the surface, it seems they are just joking with each other except for the final question and answer.

In the first two lines of Dōgen’s verse, he is referring to the difference between Farong before and after meeting Daoxin, and also the difference between young Farong before meeting Daoxin and the two Zen adepts:

Carrying flowers, hundreds of birds made offerings to Niutou.

Touzi [Datong] appeared to be selling oil.

The first line is about the story of Nitou Farong and Dayi Dioxin. Farong was practicing meditation, seeking awakening to become a buddha. He had a mysterious power that attracted spiritual being and animals, so that they made offerings to him. But after Farong attained the Way, they could not see him and stopped making offerings. This is an important point in Dōgen’s teaching and practice. Dōgen introduces several more examples like Farong in Shōbōgenzō Gyōji (行持, Continuous Practice). The first one is Yunju Daoying (雲居道膺, Ungo Dōyō, ? – 902), the main heir of Dongshan, the founder of Chinese Sōtō School of Zen:

Great Master Hongjue of Mount Yunju, when long ago he was staying at the Sanfeng Hermitage, was sent food from the kitchen of the devas. Once, the Great Master visited Dongshan, ascertained the great way, and then returned to the hermitage. The emissary of the devas, once again sending food, sought the Master for three days but was unable to see the Master. No longer dependent on the deva kitchens, he took the great way as his basis. We should give thought to his spirit confirms [the way].[7]

The other examples are Jingqing Daofu (鏡清道怤, Kyōsei Dōfu, 864–937), Sanping Yizhong (三平義忠, Sanpei Gichū, 781–872), Nanquan Puyuan (南泉普願, Nansen Fugan, 748–835), and Hongzhi Zhengjue (宏智正覺, Wanshi Shōkaku, 1091–1157). About the reason why mysterious beings could not see the Zen masters after they attained the Way, Dōgen wrote:

Among past buddhas and ancestors there were many who received offerings from the devas. However, once they gained the way, the eye of the devas did not reach them, and the spirits lacked means [to contact them]. We should be clear about this point. When the devas and spirits follow the conduct of the buddhas and ancestors, there is a path for them to approach the buddhas and ancestors; when the buddhas and ancestors transcend the devas and spirits everywhere, the devas and spirits have no means of looking so far up to them and cannot approach the vicinity of the buddhas and ancestors.

These sayings came from Dōgen’s basic point of his practice, that is, continuous diligent practice without gaining-mind (無所得の常精進). His practice is not to go to some better place within the triple worlds of samsara without escaping from samsara. He finds nirvāṇa within samsara right in his continuous practice because samsara and nirvāṇa are not two separate places.

Talented and untalented are thirty-five miles apart.

People in the past and present have expressed progress and practice.

“Talented and untalented are thirty-five miles apart,” is taken from a non-Buddhist, classic Chinese story quoted in a Buddhist text by a Tendai master. In the original story, while two people are traveling, they saw a puzzling sentence by the side of the road. One of them, a talented person, understood right away, but the other person understood only after they walked thirty miles. In the quotation in the Buddhist text, it says thirty-five miles, instead of thirty-miles. That was the difference between Manzan’s version and Monkaku’s version.

In any event, the point is that we practice based on the ultimate principle, beyond dichotomy between deluded living beings and enlightened Buddha. Our practice is not to seek buddhahood. Still, there are differences among practitioners.

In the final line, Dōgen says that buddhas and ancestors in the past and present maintain that the differences are caused by whether we make diligent effort and practice. The original expression Dōgen used is 進 (shin) and修 (shu). The character進 (shin) means “to progress,” or it can be abbreviation of 精進 (shōjin), which means “diligent effort” (virya pāramitā), one of the six pāramitā. This is interesting logic; we don’t practice seeking progress in order to gain awakening or to become buddha, we practice based on the ground of oneness of living beings and buddhas. Still, to understand this point, we need diligent effort to practice. In this logic, we see the interpenetration of difference and unity. Within our diligent practice without seeking anything, buddhahood, or Dharmakaya Buddha is always present and indestructible.

— • —

[1] Dōgen’s Extensive Record volume 4, Dharma hall discourse 313, p. 289 © 2010 Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, Dōgen’s Extensive Record. Reprinted by arrangement with Wisdom Publications, Inc., www.wisdompubs.org.

[2] Nancuan’s family name was Wang (王); Wang Rōshi refers to himself. This means that even though we don’t need to seek after awakening, still there is some difference between Farong and Nancuan. I think Nancuan is expressing the interpenetration of difference and unity.

[3] 是れより霊恠鬼神は供須するに地無し。

[4] Okumura’s translation in Heart of Zen: Practice without Gaining-mind (Sōtōshū Shūmuchō,1988), p.16.

[5] Zhauzhou’s question and Touzi’s answer later became a famous kōan which appears in both Blue Cliff Record case 41, and Book of Serenity case 63.

[6] Houbai (侯白) and Houhei (侯黒) were both skilled thieves. See Book of Serenity case 40: Yunmen, Houbai and Houhei.

[7] The translations from Gyōji are from Treasury of the True Dharma Eye: Dōgen’s Shōbōgenzō, Volume II (Sōtōshū Shūmuchō, 2023). p.6–56.

— • —

Translation and commentary by Shōhaku Okumura Roshi.

— • —

For further study:

See Dōgen’s Extensive Record.

> More of Dōgen Zenji’s Chinese Poems

Copyright©2024 Sanshin Zen Community