I vow with all beings:

When I’m at home

In the training temple, there are four-line verses (Skt. gathas, Jp. ge) to be chanted for a variety of daily activities. Everything from waking up in the morning to brushing the teeth to eating a meal is an opportunity to remember to practice what Buddha taught. These gathas are based on teachings from Volume 14 (Purifying Practice) of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Hoko takes a look at these sutra verses to investigate what they’re pointing to and how we can include them in our own daily practice.

When I’m at home,

I vow with all beings

to realize that “home” is empty

and escape its pressures.[1]

The first verse in the sutra starts where we all start—at home. What could be more basic and foundational? Chances are, you haven’t considered simply being at home as a practice in itself. Yet, of course, there is home and “home”—the home made up of doors and dishes and dresses, and the “home” we inhabit when we settle into non-attachment.

When we receive lay precepts, the ceremony is sometimes called zaike tokudo 在家得度: staying home and acquiring (the practice). That’s in contrast to ordination as a novice, which is called shukke tokudo 出家得度: leaving home and acquiring (the practice). Traditionally, laypeople did their practice in the context of family and job responsibilities, while the clergy left those obligations behind and devoted the entirety of their time and attention to sitting and study. Today in North America, few practitioners live in a temple full time; almost all of us are managing home lives for ourselves regardless of what kind of commitment we’ve made to the Three Treasures. If we don’t do our own laundry, cook our own meals, go get the mail and cut the grass, those things aren’t going to happen. The cat box isn’t going to clean itself.

The daily round of home life is made up of both tedious chores and special memories. It’s where the den is full of keepsakes and the basement is full of clutter. It’s where your toddler learns to crawl and where you wait up on prom night. Taking care of infants and elders, taxes and temperatures, guinea pigs and groceries becomes a moving, changing mosaic of activity. Days are full and closets are full and mouths are full. But wait—”home” is also empty?

Home, like everything inside and outside of it, is the very embodiment of emptiness, or suchness. Emptiness in this case means that none of it has a permanent self-nature to which we can cling. That’s because nothing comes into existence randomly. Everything arises from causes and conditions. Some kind of energy moves somewhere, or karma unfolds, and there’s the potential for something to arise. However, without the right conditions, things will go in another direction. If you try to plant a seed on a rock, it won’t grow and flower. If you have a patch of lovely soil but no seed to plant, again no flower will grow. Both causes and conditions are necessary for any particular thing to happen.

The Buddha taught that all things are impermanent, including causes and conditions and the things to which they lead. If causes and conditions are themselves changing, it stands to reason that the things that arise from them are also constantly changing. That means we really can’t cling to anything—even as something as important to us as home.

We take a lot of our self-image from our homes, and we likely consider our homes and home lives to be both expressions and explorations of who we are. Not clinging to the beliefs and belongings we associate with our homes is a tall order. There’s little more personal to us than where we live and what we own. I think it’s no accident that the sutra verses start here. If we can see the emptiness of home, we’re on our way to seeing the emptiness of this one unified reality.

But why would we want to do this? Why disenchant ourselves from something as wholesome and comforting as home? Why seek another “home” when this one seems perfectly fine?

Not having a place to call home can indeed be disconcerting. I lived in the Twin Cities for the first 45 or so years of my life. Then all at once I rented out my house, put everything I owned in storage, quit my government job of 16 years, and went to train in Japan. I didn’t know how long I’d be there or what I’d be doing when I came back. When I returned I immediately went to run the Zen center in Milwaukee, I city in which I’d never lived before. From there, two years later I went to work at Hokyoji in southern Minnesota, just off the Iowa border, and after another three years I came to Sanshin in Indiana. Along the way, I realized that I felt like I no longer had a permanent home. After nearly five decades in one place, suddenly I was pulling up sticks and moving over and over again.

Not only was I now leading a nomadic life, when I went back to the Twin Cities I didn’t recognize the old, familiar places I was used to. Time and people had moved on. Buildings had been put up, renovated and torn down. My old office building was now a condo. The house in which I’d grown up had long since been sold to another family. Rural residential areas were now zoned for higher density housing and urban sprawl was worse than ever. My old home was well and truly gone.

That bothered me some for awhile. If we don’t know where we come from, we lose some sense of who we are. My family isn’t from Minnesota originally, but it was the only place I knew for many years. I envied those of my friends who had several generations in the state and felt a real connection to Minnesota culture. When I began work on my genealogy at the age of 14—long before the age of the internet, when everything had to be done by paper letters—I suspect I was trying to get a sense of where I come from. As it turns out, I had to go back six or seven generations to find ancestors and their families with deep roots in any one place. Even so, their places weren’t my places. I’d never been to them and hardly felt like I could lay claim.

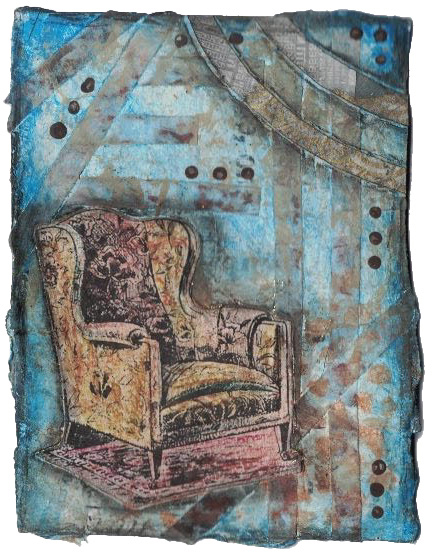

After I’d been in Indiana for about a year, a sangha member asked me whether Bloomington felt like home now. I had to say no, but I also couldn’t say where home was for me now. It’s become a moment-by-moment concept for me. In Japan, home was the storage room above the kitchen in the training temple that my roommate and I cleared out for ourselves. In Milwaukee it was the lovely little teacher’s apartment up on the second floor of the turn of the century house that serves as the temple. At Hokyoji, I lived entirely in a room of about 170 square feet over the workshop and tractor garage. All were home briefly before it was time to follow the dharma somewhere else.

All of those places are part of my story, but I don’t think I take any identity from them now. Looking back, I can see that the universe has been handing me a teaching about the emptiness of “home.” We can exist without the need to pin down home as a physical location, and on that basis we can “escape its pressures.” We can be equally at home in samsara and nirvana, living with equanimity whether we encounter shrieking cats and leaky sinks or comfy beds and perfect cups of Keemun Black. Home is where our feet are right now, because there’s nowhere else we can be.

Nonetheless, home is a charged concept. We carry a lot of shoulds about home. It should be a place of safety and security, a familiar “comfort zone,” a manifestation of self-respect, a place where we belong because we’re surrounded by other like-minded people. If we don’t associate some or all of those things with the situation in which we find ourselves, then home is somewhere else—somewhere we long to reach, where everything would be better. There’s no place like home, and this sure isn’t it.

One way to define suffering is that we want things to be other than they are, and we can’t settle down anywhere while we’re chasing after what we want and running away from what we don’t want. These are the pressures we escape when we realize what and where “home” really is. In his Zazen Yojinki (Points to Watch in Practicing Zazen), Keizan Zenji reminds us, “The Buddha said, ‘Listening and thinking are like being outside of the gate; zazen is returning home and sitting in peace.’ How true this is! When we are listening and thinking, the various views have not been put to rest and the mind is still running over. Therefore other activities are like being outside of the gate. Zazen alone brings everything to rest and, flowing freely, reaches everywhere. So zazen is like returning home and sitting in peace.”

Finding the way “home” is as simple and as difficult as opening the hand of thought. That’s when we can deeply understand that we’ve never really left the place where we belong, nor do we need to in order to find some perfect place to settle. “Why leave behind the seat in your own home to wander in vain through the dusty realms of other lands?” asked Dogen Zenji. “If you make one misstep, you stumble past what is directly in front of you.”

When we’re at home, whether in the midst of family uproar or focused solitude, let’s vow with all beings to realize that our actual “home” is empty of all of our ideas about it, all of our shoulds and attachments and stories. Let’s escape the pressures of home that come either from clinging to the one we have or restlessly looking for another. Let’s remember to practice what Buddha taught.

—•—

Next time:

Serving my parents,

I vow with all beings

to serve the Buddha,

protecting and nourishing everyone.

—•—

[1] Translations are based upon Thomas Cleary’s translation of the Avatamsaka Sutra, and have been recast by Hoko in the form of standard Sotoshu gathas.

— • —

Commentary by Hoko Karnegis

The Dōgen Institute offers a monthly series of posts by Hoko Karnegis, Senior Dharma Teacher at Sanshinji, in Bloomington, Indiana.

— • —

For further study:

> Other posts from this series

Copyright © 2024 Sanshin Zen Community