Dōgen’s Chinese Poems (66)

A Fire Boy’s Dedicated Play

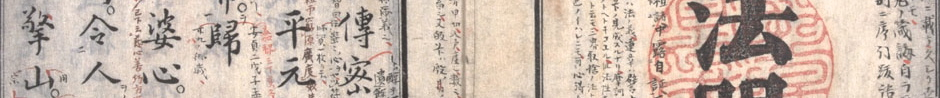

299. Dharma Hall Discourse in Appreciation of the Previous Director

謝監寺」(「監寺を謝す」)

丁童子來求火 丁童子來りて火を求む。)

驀直逢煙且莫休 (驀直に煙に逢うて且く休むことなかれ。)

弄得金星明歴歴 (金星を弄得して明歴歴たり。)

臘梅●發舊枝頭 (臘梅●發す舊枝の頭。)

● is a rare kanji which is not available in most fonts: (光+闌, ran). The right side (光) means “light,” or “to shine.” The left side shows the sound, “ran.”

The fire boy comes seeking fire.

With complete dedication, do not stop when you have only seen the smoke.

Play with the golden star (Venus), manifesting so brightly.

A December plum blooms colorfully on the tip of an old branch.[1]

This is verse 65 in Kuchūgen and is the last part of Dharma Hall Discourse (上堂, jōdō) 299 in Volume 4 of Eiheikōroku. This was given after Dharma Hall Discourse 298, on appreciating the Inō, sometime after the 8th day of the 12th month and before the 25th day of the same month in 1248. Dharma Hall Discourse 300 deals with the appointment of the new director. Manzan’s version is almost the same as Monkaku’s version but there is one character difference in the last line:

臘梅●發舊枝頭 (臘梅●發す舊枝の頭。)

A December plum blooms vigorously on the tip of an old branch.”

● is (文+闌, ran), which, in this case, means to grow vigorously beyond the frame.

A Fire Boy’s Dedicated Play

299. Dharma Hall Discourse in Appreciation of the Previous Director

Dōgen’s speech before this poem in Dharma Hall Discourse 299 is:

After relating the story about the director [Bao’en] Xuanze and the fire boy, the teacher Dōgen said: Before, when [Bao’en Xuanze] heard, “The fire boy comes seeking fire,” he did not understand, but later when he heard this he was completely awakened. Tell me, great assembly, where is the key to this change?

Now I will exert myself completely to compose a verse in order to express appreciation to Director Tai.[2]

“Director” is a translation of 監寺 (Ch. jiansi, Jp. kansu). Kan (監) means “to oversee,” “government office,” “director,” or “head official.” 寺 (Ch. si, Jp. su, ji, or tera) means “temple.” In Chanyuan Quingui (禅苑清規, Zennen Shingi, compiled in 1103 CE), the kanshi is one of the group of four temple administrators, called 監院 (Ch. jianyuan, Jp. kannin).[3] The other three administrative positions are tenzō (典座, cook), inō (維那, rector), and shissui (直歳, work leader). Regarding the director’s job, it says “the single job of director governs all the general affairs of the temple,” and mentions an extensive list of work.[4] By the time Dōgen Zenji visited China, Zen monasteries had become much larger institutions with so many things for administrators to oversee that the director’s position was divided into three; the tūsu (都寺, general director), kansu, (監寺, assistant director) and fūsu (副寺, treasurer). In Dōgen’s Pure Standards for the Temple Administrators (知事清規, Chiji Shingi), he uses both kannin and kansu for the same job. Since his monastery was not large, they probably did not need the three different directors.

In Eiheikōroku Volume 1, the collection of Dōgen’s dharma hall discourses at Kōshōji in Fukakusa, near Kyoto, we don’t find any dharma hall discourse regarding temple administrators. It was when they had the first summer practice period at Daibutuji in 1245 that Dōgen began to establish a more organized monastic system following the Chinese model described in Chanyuan Guingui (禅苑清規, Zennen Shingi). The first discourse in Eiheikōroku regarding temple administrators was given in the 12th month in 1245 in Volume 2. Dōgen gave three discourses on temple administrators in this volume: 137, a discourse in appreciation of the outgoing director; 138, in appreciation of the outgoing tenzo; and 139, on inviting the incoming director and tenzo.[5]

In his comment in Chiji shingi on the work of the director, Dōgen writes:

The director’s job is fulfilled for the sake of the public [i.e. everyone, both in the community and all beings]. To say for the sake of the public means without [acting on] private inclinations. [Acting] without private inclinations is contemplating the ancients and yearning for the Way. To yearn for the Way is to follow the Way. First read the Shingi and understand as a whole, then act with your determination in accord with the Way.[6]

In Chiji Shingi, Dōgen introduces two examples of those who clarified the great matter when serving as director.[7] The first one is the one Dōgen refers to in this poem, the example of Baoen Xuanze (報恩玄則, Hōon Genzoku, ? – ?), a dharma heir of Fayan Wenyi (法眼文益, Hōgen Buneki, 885–958). The second example is the Rinzai Zen master Yangqi Fanghui (楊岐方会, Yōgi Hōe, 992–1049) who served as the director in the assembly of Ciming Chuyuan (慈明楚円, Jimyō Soen, 986–1039).

The fire boy comes seeking fire.

With complete dedication, do not stop when you have only seen the smoke.

The first line of this poem refers to a story of a monk who was the director in the monastery of Fayan, the founder of one of the five Chinese Zen schools, the Fayan (Hōgen) School. This is the first story regarding the director in Chiji Shinji, about Baoen Xuanze. Dōgen also introduced this story in Bendōwa (辧道話) written in 1231:

Long ago, Xuanze was the director in the assembly of Zen Master Fayan.

Fayan asked him, “Director Xuanze, how long have you been in my assembly?”

Xuanze replied, “I have already been in the Master’s assembly for three years.”

The Zen master said, “You are a student. Why haven’t you ever asked me about buddha-dharma?”

Xuanze said, “I cannot deceive you, Master. Once when I was at Zen Master Qingfeng’s place, I achieved the peace and joy of buddha-dharma.”

The Zen master asked, “With which words were you able to enter?”

Xuanze responded, “I once asked Qingfeng, ‘What is the self of this student?’

Qingfeng said, ‘The fire boy comes seeking fire.’”

Fayan said, “Good words! However, I’m afraid that you did not understand them.”

Xuanze said, “My understanding is that the fire boy belongs to fire. Already fire, still he seeks fire, just like being self and seeking self.”

Fayan exclaimed, “Now I really know that you don’t understand! If buddha-dharma was like that it would not have been transmitted up to today.”

At this, Xuanze was overwrought and left [the monastery] immediately.

On the road he thought, “The Zen master is one of the world’s fine teachers, and also the great guiding teacher of five hundred people. Certainly, there must be merit in his pointing out my error.”

He returned to Fayan and, after making prostrations in repentance, asked, “What is the self of this student?”

The Zen master said, “The fire boy comes seeking fire.”

With these words, Xuanze was greatly enlightened to buddha-dharma.[8]

The position of the director is the highest among all temple administrators, and has the overall responsibility for temple affairs. The person appointed to this position must be a capable and experienced monk. Xuanze was such a person, but during the three years since joining Fayan’s monastery, he had never attended dharma gatherings such as dharma hall discourses (jōdō), minor gatherings (shōsan), etc. to listen to Fayan’s dharma teachings. He did not visit the abbot’s room to ask dharma questions. When asked the reason, Xuanze said that he had attained awakening when he practiced with another master in the past, therefore he did not need to listen to other teacher’s dharma teachings anymore.

Fayan asked with which saying he had attained awakening. According to Xuanze, he asked his previous teacher “What is the self of this student [Xuanze himself]?” Then the teacher said, “The fire boy comes seeking fire.”

“The fire boy” is a translation of 丙丁童子 (Ch., Bingding Tongzi, Jp. Heitei Dōji) . Both 丙 (Ch. bing, Jp. hei) and丁(Ch. ding, Jp. tei) mean “fire.” They are the 3rd and 4th of the ten celestial stems (a Chinese system of ordinal number words including two types each of wood, fire, earth, metal, and water). 童子 (dōji) means a boy. In ancient China, the fire boy is considered to be the attendant of the god of fire. At Chinese Zen monasteries, a young novice who took care of lighting lanterns when it became dark was called by this name.

Upon hearing this saying, Xuanze had understood that, even though the fire boy belongs to fire, still he seeks fire; it is just like already being self, still seeking self. Therefore, Xuanze understood that since he was already his own self, he does not need to seek after anything outside. That was why he did not attend Fayan’s dharma teaching.

Then Fayan said that even though the saying is fine, Xuanze did not understand the meaning of it. Xuanze became angry and left the monastery right away. On his road, he reflected to himself and thought that there must be some reason for Fayan’s admonition to him. He returned to the monastery, made repentance to the abbot, and asked the question, “What is the self of this student?” Fayan repeated exactly the same thing as Xuanze’s previous teacher, “The fire boy comes seeking fire.” Even though the saying is exactly the same, this time, Xuanze was greatly enlightened to buddha-dharma.

In Bendōwa, Dōgen introduces this story as evidence of the counter-argument to the following idea:

In buddha-dharma, those who thoroughly understand the principle that mind itself is Buddha, even if they do not chant sutras with their mouths or practice the buddha way with their bodies, still lack nothing at all of buddha-dharma. Rather simply knowing that the buddha-dharma exists in the self from the beginning is the perfect accomplishment of the Way. Outside of this, you should not seek from other people, much less take the trouble to engage the Way in zazen.[9]

However, in this poem, Dōgen refers to Xuanze’s example to say that we should not stop studying and practicing even after we have had some experience or understanding about the self and the dharma. That is the meaning of the fire boy seeking the fire. We should not stop seeking when we only see some smoke of the fire, meaning the conceptual understanding of the saying.

In the second example story regarding the director in Chiji Shingi, Yangqi Fanghui, who served as the director in Ciming’s assembly, had the opposite problem as Xuanze’s. As Ciming served as the abbot of a few monasteries, moving from one monastery to the other, Yangqi had been always supervising temple administrative affairs. Even though he had been practicing with the master for a long time, he still had not yet had an awakening experience. When Yangqi attended a dharma gathering and asked a question, Ciming said, “Director, go for now [and attend] to the profusion of affairs.” Relationships between the abbots and the director are various.

Play with the golden star (Venus), manifesting so brightly.

A December plum blooms colorfully on the tip of an old branch.

“Golden star” is a translation of 金星 (Ch. jinxing, Jp. kinsei) literally “golden star,” the Chinese name for Venus. Shakyamuni Buddha had awakening while sitting under the bodhi tree in the dawn when this morning star was shining brightly. “To play with the golden star” means to continue studying, practicing, and working being illuminated by the Buddha’s awakening. In doing so, the director manifests the Buddha’s awakening brightly in his practice and work of taking care of day to day, seemingly mundane affairs for the sake of the monastic community.

It seems that changing the temple administrators was done at the end of the year at Eiheiji. This dharma hall discourse was given sometime between Buddha’s Enlightenment Day (the 8th day of the 12th month), and New Year’s Day. “December lotus flower” is used as an example of something extremely rare and precious, or not possible, the same as an uḍumbara flower, which blooms every three thousand years. But “a December plum blossom” as in this poem, is the only actual flower that is blooming in the snow in the remote mountain where Dōgen lived; it is the sign of spring. “An old branch” refers to the long, old tradition of the buddhas and ancestors.

— • —

[1] Dōgen’s Extensive Record volume 4, Dharma Hall Discourse 299, p.279 © 2010 Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, Dōgen’s Extensive Record. Reprinted by arrangement with Wisdom Publications, Inc., www.wisdompubs.org.

[2] Dōgen’s Extensive Record, Volume 4, p.279.

[3] 院 (Ch. yuan, Jp. in) means “mansion,” “palace,” or refers to a temple.

[4] See The Origin of Buddhist Monastic Codes in China (translation by Yifa, Kuroda Institute, 2002), p.150–151, or Dōgen’s Standards for the Zen Community, p.152.

[5] Dōgen’s Extensive Record, Volume 2, p. 165-8.

[6] Dōgen’s Standards for the Zen Community p. 155

[7] Ibid. p.132 -134.

[8] I made some changes to the translation by Shohaku Okumura & Taigen Daniel Leighton in The Wholehearted Way: A translation of Eihei Dōgen’s Bendōwa (Tuttle, 1997), p. 37–38.

[9] Ibid., p.37.

— • —

Translation and commentary by Shōhaku Okumura Roshi.

— • —

For further study:

See Dōgen’s Extensive Record.

> More of Dōgen Zenji’s Chinese Poems

Copyright©2023 Sanshin Zen Community