Dōgen’s Chinese Poems (42)

Verses of Praise on Portraits

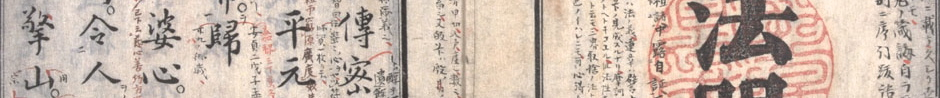

真賛 Shinsan 5

Master Butsuju [Myōzen]

「佛樹和尚」 (「佛樹和尚」)

His everyday practice of the way was thorough and intimate.

When he passed into nirvāṇa his face was fresh.

Tell me, what is his affair today?

Since the vajra flame, he manifests his true body.[1]

平生行道徹通親 (平生の行道徹通親し、)

寂滅以來面目新 (寂滅以來面目新なり)

且道如何今日事 (且く道え如何今日の事、)

金剛焔後露眞身 (金剛の焔後眞身を露す)

— • —

This is verse 41 in Kuchūgen and Shinsan 5 in Volume 10 of Eihei Kōroku (Dōgen’s Extensive Record). Monkaku’s version and Manzan’s version have no differences between them.

Master Butsuju [Myōzen]

Myōzen was one of Dōgen’s early teachers. He was sometimes called Butsuju-bō. Butsuju (仏樹, Buddha Tree) is Myōzen’s bōgō (房号), the name of a monk’s hermitage or cell. In Japan, Buddhist monks were known by the name of the place they lived, such as their temples (for example, Eihei Dōgen), or by the names of their hermitage or cell within a larger temple. Dōgen Zenji was also sometimes known by his bōgō, Buppō-bō (仏法房, Buddha Dharma) even though it is not certain if he lived in a hermitage by that name or if it was just a kind of a nickname. This custom came from China, where a person’s real name was not usually used outside one’s family. I suppose this poem was composed when Myōzen’s portrait was painted and Dōgen was asked to write a praising poem for the painting.

Myōzen (1184–1225) was a Rinzai Zen master, but since he died young in China, he is unknown in the Rinzai school. Almost all the information we know about him is from what Dōgen wrote or said about him. Myōzen was born in Iga (伊賀) or Ise (伊勢) Province in today’s Mie Prefecture. These provinces are next to each other. Dōgen wrote that Myōzen was from I-shū (伊州), which is usually an abbreviation for Iga. The abbreviation for Ise is Se-shū (勢州) but some scholars think this means Ise. We don’t really know where he was born and who were his parents.[2] When he was eight years old, he left his family and went up to Mt. Hiei to live with his teacher Myōyu. He was ordained as a monk at Mt. Hiei when he was sixteen years old. Later, he practiced Zen with Eisai at Kenninji, Kyoto. After Eisai’s death, in 1217, Dōgen began to practice Zen with Myōzen. In 1223, Myōzen went to China with Dōgen and two other monks. In Zuimonki, Dōgen talked about Myōzen’s decision to go to China even though his teacher Myōyu at Mt. Hiei was on his death bed and had requested Myōzen to postpone the travel until Myōyu’s death.[3]

After practicing at Tiangtong monastery for about two years, Myōzen passed away. Dōgen wrote about Myōzen’s death and his cremation ceremony in Note on Transmitting [Master Myōzen’s] Relics:[4]

On the eighteenth day of the fifth month of the first year of Baoqing Era [1225], he became ill. On the twenty-seventh day of the same month in the hour of the dragon [between seven and nine a.m.], he adjusted his robes, sat upright and entered nirvāṇa. Monks gathered like clouds and made prostrations [to Myōzen’s casket]; lay people came like mist and showed their respect by putting their head on the floor. After completing the funeral ceremony, during the hour of dragon on the twenty-ninth day of the same month, the cremation took place. The fire changed its light into five colors. The assembled people admired this and said, “Certainly relics (śarīra)[5] would appear.” As they said, when we saw the site of the cremation, we found three pieces of white crystal-like relics. When people reported this to the temple, all the monks in the assembly gathered together and honored [the relics] by having a ceremony. Later people continued to pick and collected more than three hundred sixty pieces [of relics].[6]

Dōgen took Myōzen’s relics back to Japan and gave part of them to Myōzen’s female student named Chi (智) together with the Note. In this praising poem, Dōgen writes about Myōzen’s cremation.

Dōgen practiced with Myōzen as his disciple for about nine years, from 1217 to 1225. Right before Myōzen’s death, on the first day of the fifth month in 1225, Dōgen first met Tiantong Rujing; later he became a dharma heir of Rujing. Dōgen referred to Myōzen and Rujing as his late masters. He gave dharma hall discourses on the anniversary of Myōzen’s death. Two of them are included in Eihei Kōroku.[7]

His everyday practice of the way was thorough and intimate.

When he passed into nirvāṇa his face was fresh.

In the first line, Dōgen praised Myōzen for his day-to-day practice being thoroughly penetrated and intimate with the buddha way. Myōzen must have been a well-known venerable master even before going to China. At the end of Postscript for Myōzen’s Certificate for Receiving the Vinaya Precepts (明全戒牒奥書, Myōzen Kaichō Okugaki), Dōgen wrote that Myōzen was the preceptor who gave the bodhisattva precepts to the retired emperor, Go-Takakura. Unfortunately, Myōzen left no writings, not even a poem. Probably he was not an eminent scholar or a talented poet, but rather, a quiet, practical, and down-to-earth person. His teacher Eisai put emphasis on keeping the precepts. It is said that Eisai received the Vinaya Precept from his Chinese master. This was very unusual for a monk from the Japanese Tendai tradition. Saichō, the founder of the Tendai school, gave up the Vinaya Precepts and discontinued the practice of receiving them in his school. Myōzen might be a faithful dharma heir of Eisai on this point. In Dharma Hall Discourse 435 on the occasion of Myōzen’s memorial day in 1251, Dōgen quoted the famous poem from the Dhamma Pada, “Not performing any evil, respectfully practicing all good, purifying one’s own mind, this is the teaching of all buddhas,” showing a close connection to the precepts.

In the second line, Dōgen refers to Myōzen’s entering nirvāṇa, that is, his death. Dōgen says that when Myōzen died, and even today, his face (面目, menmoku) is always fresh. This does not mean his physical face; menmoku is used as an abbreviation for the “original face” (本来の面目, honrai no menmoku). His continuous practice, including his passing away, is the manifestation of his true face as a Buddhist monk.

Tell me, what is his affair today?

Since the vajra flame, he manifests his true body.

In the third line, Dōgen is addressing the person for whom Myōzen’s portrait was painted, probably Myōzen’s disciple or a lay supporter: what is Myōzen doing today? Dōgen is asking to us too, “Do we continue to live following Myōzen’s example?” Our practice is Myōzen’s affair today. Myōzen is not gone. He is still living together with the people who practiced with him, Dōgen, and us–all who are walking the bodhisattva path. Are we living in the same way Myōzen lived, continuing his teaching and practice?

In the final line, “the vajra flame” refers to the fire that burned Myōzen’s body at his cremation. However, this word has another meaning which comes from the Song of Enlightenment (証道歌, Shōdōka), the classic Zen poem:

A man of great will carries with him a sword of wisdom,

Whose flaming Vajra-blade cuts all the entanglements of knowledge and ignorance;

It not only smashes in pieces the intellect of the philosophers

But disheartens the spirit of the evil ones.[8]

大丈夫秉慧劒。

般若鋒兮金剛焔。

非但能摧外道心。

早曾落却天魔膽。

“Vajra-flame” refers to the flame of prajñā (wisdom) which extinguishes the fire of the three poisonous minds, greed, anger/hatred, and ignorance. This is like the story of Shakyamuni Buddha subduing the fierce nāga king’s fire with his own fire of wisdom.[9] I think Dōgen means that Myōzen became the vajra-flame, his true body, through his passing away. Dōgen is asking if we live with awakening of emptiness, impermanence and no-self as Myōzen did.

— • —

[1] (Dōgen’s Extensive Record 10 – Verses of Praise on Portraits 5, p.601) © 2010 Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura, Dōgen’s Extensive Record. Reprinted by arrangement with Wisdom Publications, Inc., www.wisdompubs.org.

[2] Tanahashi’s translation says that he was from Iyo (伊予) Province, but I think it is a mistake. Iyo (伊予) was in Shikoku, its abbreviation is Yo-shu (予州). See Enlightenment Unfolds: The Essential Teachings of Zen Master Dōgen (Edited by Kazuaki Tanahashi, Shambhala), p.30.

[3] See Shōbōgenzō-Zuimonki (translation by Shohaku Okumura, Sōtōshū Shūmuchō, 1988) 5–12, p.178–80.

[4] Jp. 舎利相伝記, Shari-soden-ki.

[5] For more information about śarīra, see: Śarīra – Wikipedia.

[6] Okumura’s unpublished translation.

[7] See Dharma Hall discourse 435 and 504 in Dōgen’s Extensive Record (translation by Taigen Dan Leighton and Shohaku Okumura) p. 390–91 and p. 450. It is not known if Dōgen gave more dharma discourses for Myōzen which were not recorded, or if he gave them only twice, in his last years, 1251 and 1252. He also gave dharma discourses for his late parents in 1251 and 1252.

[8] D.T. Suzuki’s translation (Manual of Zen Buddhism), p.95. “The philosophers” refers to non-Buddhist teachers.

[9] See Gotama Buddha: A Biography Based on the Most Reliable Texts (by Hajime Nakamura, Kosei Publishing Co.), p.294.

— • —

Translation and commentary by Shōhaku Okumura Roshi.

— • —

For further study:

> More of Dōgen Zenji’s Chinese Poems

Copyright©2021 Sanshin Zen Community