What does transmission mean? Is it a “thing” that is transmitted?

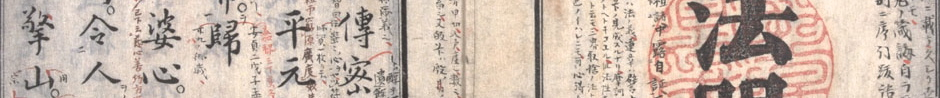

The World-honored One, before an assembly of millions on Vulture Peak, picks up an uḍumbara flower and winks. The assembly is totally silent. Only the face of Venerable Mahākāśyapa breaks into a smile. The World-honored One says, “I have the right Dharma-eye treasury and the fine mind of nirvana; along with the saṃghāṭī robe, I transmit them to Mahākāśyapa. The World-honored One’s transmission to Mahākāśyapa is “I have the right Dharma-eye treasury and the fine mind of nirvana.”[1]

In this translation of a passage from Shobogenzo Butsudo, “right Dharma-eye treasury” in Japanese is shobogenzo, and “the fine mind of nirvana” is a translation of nehan myoshin; another translation might be “wondrous mind of nirvana.” “The saṃghāṭī robe” is the okesa.

This is the famous story of the first dharma-transmission, from Shakyamuni to Mahakasyapa, without using any words or concepts. This is called the transmission from mind to mind, or in Japanese isshin and denshin, mind is transmitted with mind. The Dharma, without any words or concepts or verbal teaching at was transmitted. People in so-called Zen school thought this was the origin of their tradition.

The word in “transmission” in Japanese is fuzoku; another possible translation is “entrust.” The idea of transmission came from the Chinese family system. I don’t think this is an Indian idea or concept. Within Chinese family systems, within the family tree, father to son and father to son, the family position or profession and property is transmitted from the father to the oldest son. The oldest son inherits from the father. This is the original idea of dharma-transmission. As when family property is transmitted from father to son, this strange thing called Dharma is transmitted from teacher to disciple.

I think this idea of dharma-transmission was created in China. It’s said that until the separation between Northern and Southern schools, between Eno (Huineng) and Jinshu, there’s no such idea of dharma-transmission or lineage. It’s after the sixth ancestor that this concept of dharma-transmission, that I receive or transmitted this person’s Dharma, became very important. Before that, I think they did have the idea of “I receive the teaching from this person, and I transmit this teaching to the next generation,” but that initially was not so important. Yet after one person created the story of dharma-transmission from the fifth ancestor to the sixth ancestor, the authority and the authenticity of that person (Eno) depended thoroughly on this dharma-transmission.

When Eno received transmission, he was not a monk yet, he was a lay person. How could he become the sixth ancestor, even though he was not even a monk? The basis for Eno as a legitimate successor of the fifth ancestor was only this mind-to-mind transmission. Even though Eno had not even received the Vinaya precepts and become a monk, somehow this was transmitted. After that, lineage and transmission became really important. From that point on, they created a family tree.

Bodhidharma came around the beginning of the sixth century. The beginning of the seventh century is the time of the fourth and fifth ancestors. It seems like it’s historically true that Bodhidharma had a disciple whose name was Huiko or Eka, but the relationship between Eka and the fourth ancestor Dōshin is not clear at all. In order to make this connection someone created an image of the third ancestor, Sosan. The famous poem Shinjinmei was composed after they made this connection. Historically speaking, the connection between these groups is not really clear.

This connection was made after the sixth ancestor, in order to make the family tree authentic or legitimate. Groups started to say “my lineage came from Bodhidharma.” Another point is that the sixth ancestor Huineng, as a historical person, was not so active. Jinshu, the founder of the Northern School was much more active and well known. But Huineng became the sixth ancestor because of the activity of one of his students, Jinne. Jinne was the person who created the story of dharma-transmission from the fifth ancestor to Huineng. The story of two competing dharma poems written by Huineng and Jinshu is fictitious, of course. It’s not a true historical event, because Jinshu practiced with the fifth ancestor in his early career, and he became independent much earlier than the fifth ancestor’s death. So there’s no chance the Jinshu and Huineng competed when the fifth ancestor was dying. If you read John McRae’s book [Seeing through Zen] this is really clear.

After the time of Baso and Sekito, Baso’s school became really popular and big, and Sekito’s school was not so big. The Soto School or Soto-shu, came from Sekito’s, and the Rinzai School is from Baso’s. The relation between Baso’s and Sekito’s schools and Huineng is actually not clear. In the lineages, Nangaku Ejo was placed between Baso and Huineng, and Seigen Gyoshi between Sekito and Huineng. But these two are the most inactive people among Huineng’s disciples. Scholars think they existed historically, but the connection between Baso and Nangaku was not clear. There is the story of polishing a tile, but that is the only connection. So that might be a made-up story by a later person. Sekito’s and Seigen’s connection was also not so clear. Today scholars think this connection was also created at the same time; there are many other examples. In order to make their group kind of a legitimate dharma-descendant of Bodhidharma, groups made a connection. That is the theory of modern skeptical scholars. I think that is possible. I don’t believe the historical lineage, but I don’t necessarily believe those scholars’ theories are true, because I don’t know. But I think that these explanations are possible.

This idea of transmission clearly came from the Chinese idea of the family system. This idea of transmission has something to do with authority and orthodoxy. Dōgen seems to believe the story of Mahākāśyapa’s transmission was true, but I don’t believe this. This is a story created in the tenth century, during the Song dynasty of China. We can’t find this story in any writings before that, so this is a made-up story by people in so-called Zen school. However, Dōgen Zenji thought this is true. That might be another point we have to consider, whether this is true or not. If we don’t think this is true, then what shall we do? Dōgen said that great Buddhas like Dharmakaya, Sambhogakaya, and Nirmanakaya were not true, but that the historical Buddha is true, and this story of Mahākāśyapa’s transmission is the way Dharma has been transmitted from Shakyamuni to Mahakasyapa and through Tendo Nyojo to Dōgen. But now we can see this is not true either, so we have to do something. Until about fifty years ago, all “Zen Buddhists” believed this is true. Now we are in a time of change or transition, to see whether we want to continue this tradition or if we want to change the tradition. I have no answer yet. But when we study Dōgen, we have to keep this in mind. Since he negated some Mahayana traditions or other Buddhist traditions, what should we do about this tradition?

In Uchiyama Roshi’s teisho on Bendowa, he says there is nothing to transmit and yet something is transmitted. That’s why this is called wondrous dharma. This is not a “thing” but a lifestyle, or life attitude that has been transmitted from teachers to students. If I hadn’t met, practiced, and studied with my teacher, I would have no idea this way of life was possible. This is something transmitted, but this is not a thing. This is not a written teaching. This is an actual way or attitude of life. Perhaps “recognition” might better than “transmission.” We have to think whether this concept of “Zen dharma-transmission” still works or not in modern times— it’s a point we have to consider.

— • —

[1] From Shobogenzo Butsudo. Nishijima & Cross’s translation is in Master Dogen’s Shobogenzo, Book 3, p. 63.

— • —

Commentary by Shōhaku Okumura Roshi

The Dōgen Institute offers an occasional series of questions from students with responses from Okumura Roshi about practice and study. These questions and responses are from Okumura Roshi’s recorded lectures, and are lightly edited.

— • —

For further study:

-

- Listen to Okumura Roshi’s recorded lectures on Bendowa.

- Read John R. Mcrae’s Seeing through Zen.

> Other Questions and responses

Copyright 2019 Sanshin Zen Community