“It’s true that we are all different squashes . . . some are bigger and some are smaller . . . some are rounder and some are longer. But even if we are different, we are all connected. We are all growing together. We don’t have to be such squabbling squashes.”

The following is excerpted from a talk given at Zen Mountain Monastery, courtesy of Dharma Communications. See below for a recording of the full talk.

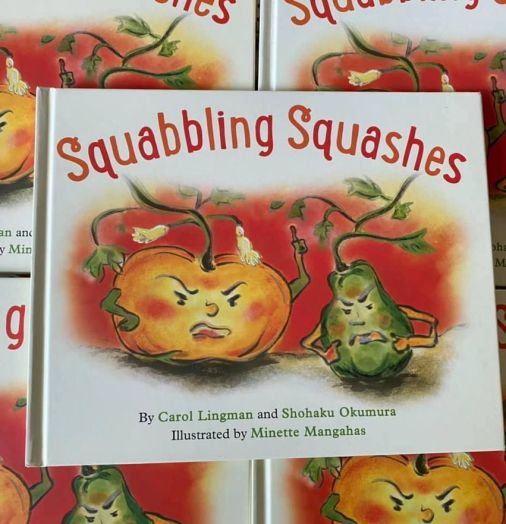

I’d like to introduce a new book published just last month from Wisdom Publications. It is a children’s book entitled Squabbling Squashes. It is not a difficult story. The monks grow squashes in the garden at their temple, and those squashes start to squabble. They argue and fight with each other about who is the best squash. Then a monk comes and asks them to sit quietly, and he teaches them how to do zazen, and they calm down. The monk asks them to put their hands on their heads. The squashes find something strange on their heads. It is a vine, and they see that they are all connected. They are living as part of the entire plant of squashes. And so, they calm down and become harmonious again.

If you have read Opening the Hand of Thought by my teacher, Kōshō Uchiyama Rōshi, you may remember that this story came from that book. When Uchiyama Rōshi introduces this story, he is talking about what is the self when we practice zazen. In Chapter five of Opening the Hand of Thought, “Zazen and the True Self,” Uchiyama Rōshi talks about what is the actual self that we are. He said there are two layers of one self. One layer is the self that is defined in comparison with others.

But Uchiyama Rōshi says this is not the only way we understand who we are and he introduces this story. The story means we are connected with all other beings and living the same life. That second layer of self is called universal self in this translation, or all-pervading self, or in more traditional Zen terms, something like “original face of the self.” In Dōgen’s unique expression, it is called jin issai jiko. Jin is all or whole, issai is everything, and jiko is the self. We are the self together with all beings without any exceptions. We are living together with all beings and are part of this interconnectedness.

Usually, we think we are independent and we compete with others and we argue. There are so many squabbling squashes in this world. Even though we are fruits of this huge tree of life, yet we think you are not them, they are not me, and I am not them. That is a correct way of thinking, but we are “1” as one of them and yet this “1” has no substance, as Buddha said. It is simply the collection of five aggregates within causes and conditions throughout space and time. This “1” individual person doesn’t really exist as a permanent independent being that can exist without relation with others.

When we study Buddhist teachings, we understand that even though we think we are one individual person (“1”), yet we are actually “0.” “0” is shunyata. When we see we are not an independent being that can exist without relation with others and therefore we are “0,” then we start to find relation with others. We are all connected because we are “0,” we are empty, we are shunyata. We find this entirety of interconnectedness is “me,” is the self.

Uchiyama Rōshi talks about only two sides: the individual being as “1,” and infinity or all-pervading self. But between “1” and infinity (∞) I think it is helpful to understand we are “0.” So when I give a talk about zazen, I almost always draw this diagram and say “1=0=∞.”

In the process of studying what he wrote in this book, I found that knowing this zero-ness or emptiness is important. When we only see the individual conditioned self or the all-pervading universal self, we often think, “This is bad; this is good.” and we think we have to transform our self from our conditioned self to the universal self. We think that to live the universal self is a good thing, an enlightened way of life. But I found that this is not what Uchiyama Rōshi said. To understand his point, it is important to see this zero-ness or emptiness of the self. It also means this individual conditioned self is not something we need to negate, but is very important. This individual self, being free from clinging, is the only thing I can use to express zero-ness and infinity.

So, it is important to awaken to the reality of emptiness and all interconnectedness through our particular body and mind, our particular collection of five aggregates. This conditioned self is the only tool I can use to practice and share with others. In order to share Buddhist teaching and practice, I have to share this conditioned karmic self. Otherwise, there is nothing I can do.

So, it is important to awaken to the reality of emptiness and all interconnectedness through our particular body and mind, our particular collection of five aggregates. This conditioned self is the only tool I can use to practice and share with others. In order to share Buddhist teaching and practice, I have to share this conditioned karmic self. Otherwise, there is nothing I can do.

To me, within those three aspects of our self, there is no good or bad, superior or inferior, something to negate or to cling to. But the three aspects are three aspects of this being. At the same time there is no way we can negate any of those three aspects.

It is a really important point that when we practice zazen to see the three aspects of our self. We have so many squabbling squashes in this world today—so this teaching of finding something strange that connects ourselves with others, and finding that we are living together with all beings, is really a meaningful teaching. Even though Uchiyama Rōshi’s book, Opening the Hand of Thought, was written fifty years ago, what he wrote is still valid in this world today.

Listen to the whole talk:

https://zmm.org/podcast/the-interdependence-of-squabbling-squashes/

Squabbling Squashes are available here from Wisdom Publications.

— • —

See our publications page for a complete listing.

Copyright 2021 Sanshin Zen Community